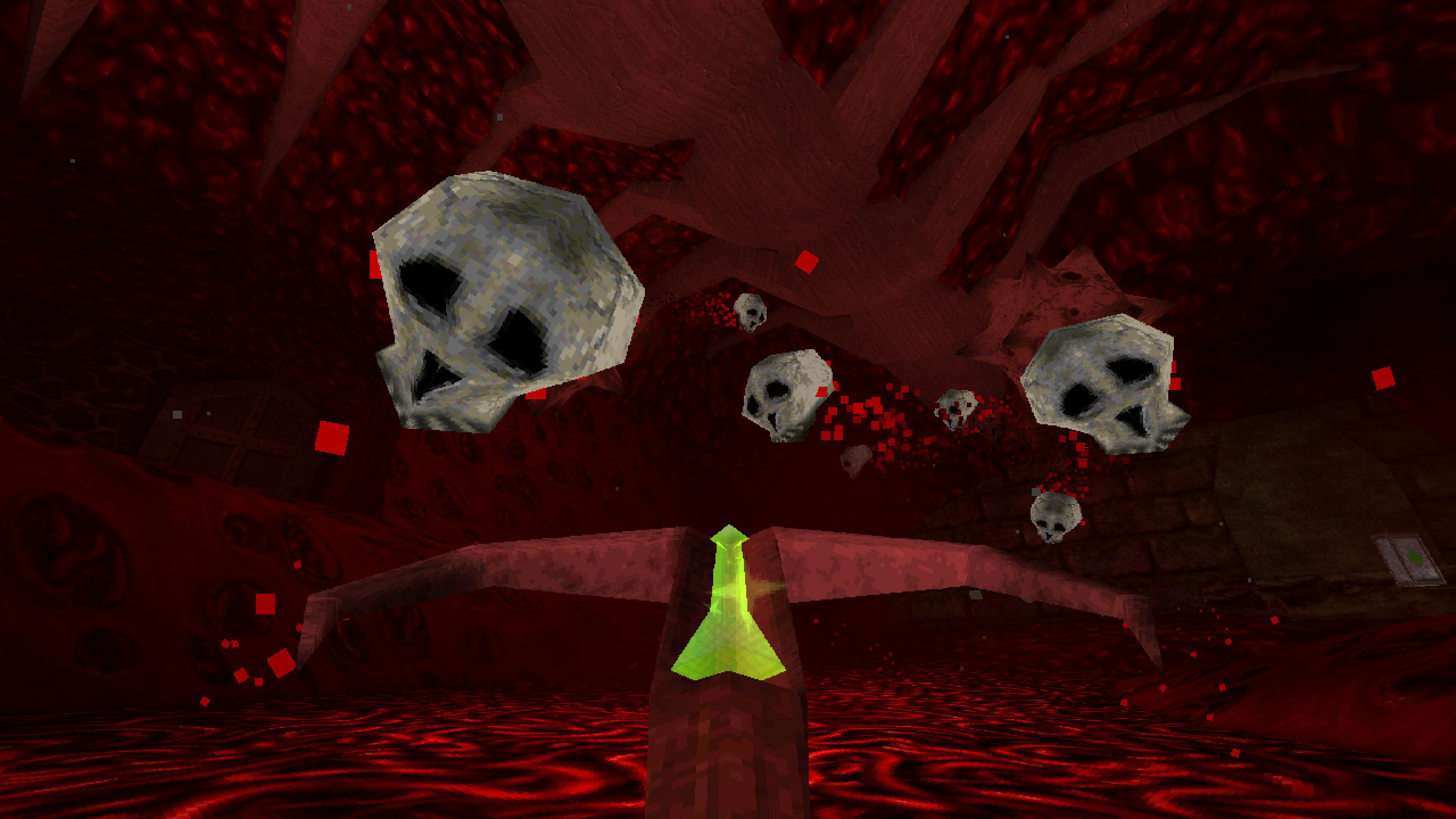

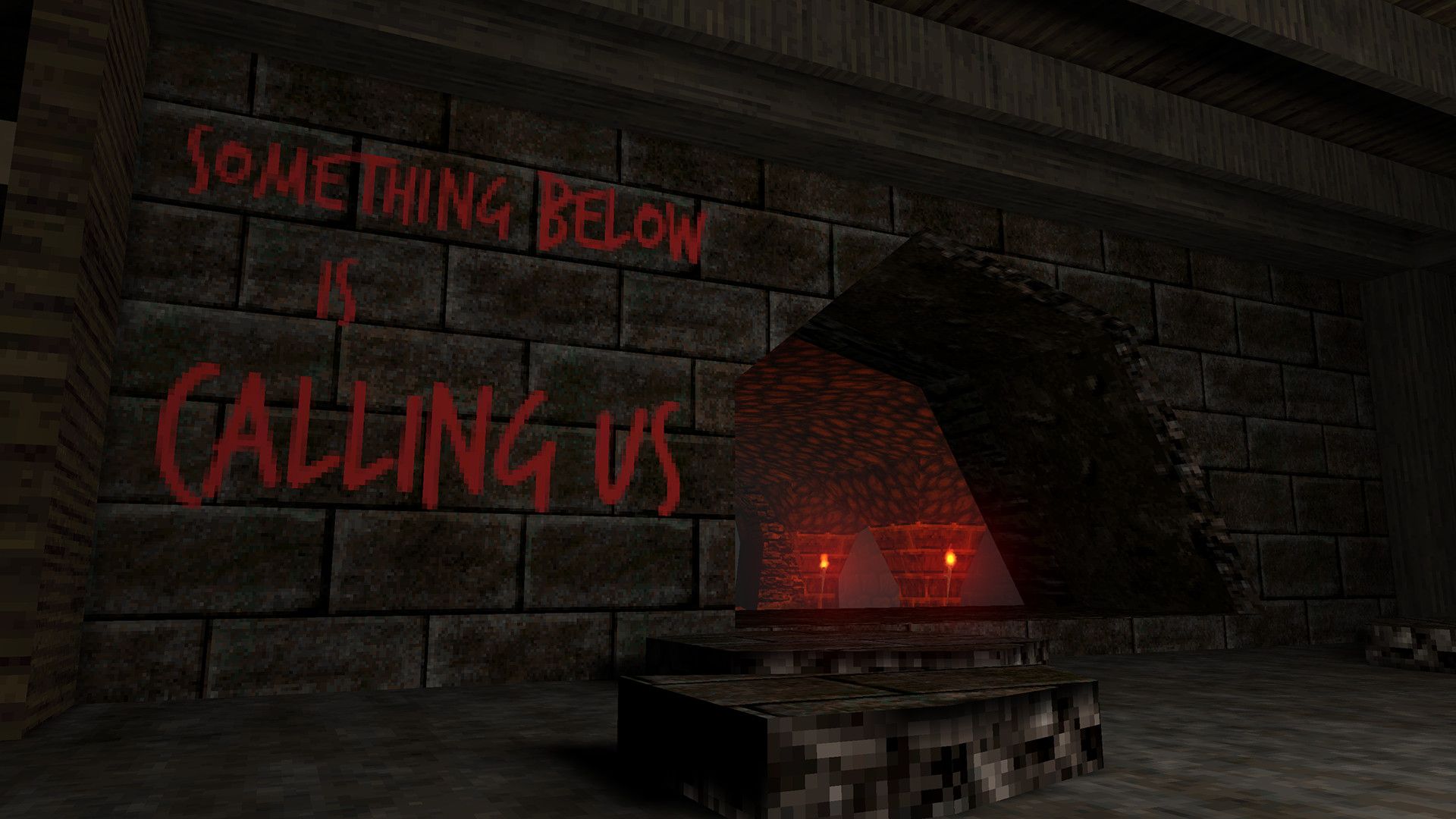

It’s a familiar feeling for some - a rarity for others - and one I’ve wrestled with on and off for years, as a lover of first-person games that move at 100mph. The kind that Dave Oshry, head of New Blood Interactive, specialises in. “Especially with our games, you move and bump around pretty fast, so it’s important to make sure we’ve got options,” he says. “We try to have as many movement, camera and accessibility options as we can.” Oshry has overseen the release of modern retro classics like Dusk and Amid Evil, and kept his customers very happy. “It’s been a long time since we’ve gotten a complaint about motion sickness,” he says. By his own admission, however, he isn’t clued up on the science behind in-game nausea. For that, I talked to Séamas Weech, a postdoctoral research fellow at Montréal’s prestigious McGill University. Weech has spent many years studying perception and sensory stimulation. He primarily works in VR - part of his training was funded by Oculus, in the interest of exploring “blue ocean approaches to solving cybersickness” - but much of his expertise applies to 3D games in general. Once you’ve heard him explain cybersickness, you won’t wonder why games sometimes make us feel ill. You’ll wonder how we ever made it through a single GoldenEye level without barfing. Imagine you’re moving through a corridor - not a particularly taxing stretch of the imagination for anybody who’s played an FPS before. In the central part of your vision, almost none of what you see moves very quickly. Instead, your brain relies on the visual elements passing by in your periphery to work out how your body is moving. “That’s the way that light flows on your retina - things at the edges move quickly,” Weech says. “And so those parts of your visual field are naturally very useful. There’s a direct loop between that visual input and the body’s posture and estimation of its state in the world.” The problem with video games - not just in VR, but also those played on TV screens or monitors - is that they introduce a mismatch. They show you visual motion that stimulates the wide part of your field of view, convincing you that you’re moving. But since you’re actually sitting or standing still, games don’t give you the inner ear feedback you’d normally expect while walking or running. “You don’t get the inertial motion cues,” Weech explains. “The force inside of your vestibular system.” That missing information, combined with the jarring visual input, can trigger warning signs in the brain. “When something like that usually happens in nature it means that you’ve ingested some sort of toxin or your body’s not functioning correctly,” Weech says. “So it should have this emetic response to deal with that.” Hitman fans, with their understanding of poisons, know exactly what an emetic response looks like - a whole lot of vomiting. By making you feel sick, your body is actually trying to keep you safe from poison. Little does it know you’re merely trying to speedrun E1M1 in Quake. When shooters introduce extra movement, like head bobbing, the issue only gets worse. “It’s an artificial stimulus that doesn’t relate to anything you’re really feeling physically,” Weech says. “If you see a head bob up and down, your brain wants to interpret and integrate it. But it can’t, because it doesn’t match with all of the other information. It’s a whole disaster for your brain to deal with that kind of thing. That’s really terribly nauseating.” Combine these factors with a breakneck movement speed, like that seen in the classic shooters of the ‘90s, and you’re asking for trouble. “It’s even more of a challenge for your brain,” Weech says. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone complain about a walking simulator-type game with respect to comfort, and there’s a very good reason for that.” Over the years, developers have empowered players with ways to counteract nausea. Head and weapon bobbing can be easily disabled in New Blood’s games, and that all-important peripheral vision can be tweaked to personal taste. “Lower FOV will keep your head a bit more centered,” Oshry says. “I think people who get motion sick will turn it down - turning the FOV up to 120-plus can definitely induce some sickness. FOV sliders are really easy to add, so obviously we have them in all of our games.” With the rise of the Nintendo Switch, however, a new frontier for nausea has opened up. While the newly released port of Dusk on Switch plays beautifully, I can’t finish the first stage without feeling some sickness. It’s not a problem unique to Dusk - from Doom 2016 to Void Bastards to Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, the handheld FPS simply doesn’t agree with me. Weech suspects he knows why. “What I would assume is going on is that a lot of it is related to eye strain,” he says. “Neck strain as well, because you’ve got to keep a much more steady head if your fixation target is smaller. Maintaining a very rigid neck state is definitely going to provoke a headache, and in some cases nausea too.” These factors can be grouped under oculomotor discomfort, which describes general visual fatigue. “Those things are really strongly challenged by working on small screens,” Weech says. “You have to really strain to resolve the visual detail, because all of the features of the screen are going to be tiny.” It’s a problem that’s only likely to become more widespread with the launch of the Steam Deck, which will make thousands of games designed for large monitors playable on a handheld. “Things on PC are absolutely not designed to work on a screen that size,” Weech says. “It’s totally going to become a bigger issue.” Evidently, many players have a higher tolerance for this kind of discomfort than I do. I’m also prone to car and seasickness, which results from an inverted form of the ear-versus-eye mismatch that causes cybersickness. But Weech suggests that the increasing fidelity and sense of place available in today’s games might lead to nausea becoming more common. “You can think of it as a bit of an uncanny valley, where the closer you get to approximating reality, the more troublesome any deviations from reality become,” he says. “If you get more presence, more sense of being there, then you’re more susceptible to conflicts when they do occur.” A good example would be seeing your hands in a VR game. In principle, that extra connection to your environment is a good thing. “What it does is ground you in the environment,” Weech says. “Rather than feeling like you’re this disembodied set of eyes just kind of floating around the world, you feel much more attached to the virtual space. There’s all of this rich, sensory information telling you where you are in the environment relative to other things.” But it can backfire: “Whenever there’s a big mismatch - between how you move your head [for example], if you’re rotating it to the left and there’s some miscalibration - that’s going to be really bad if you’re very strongly immersed in the environment.” This is a roadbump that game developers have discovered for themselves. Although New Blood has never released a VR game, it has dabbled, and learned that it’s unwise to take control of the player’s head - “or else people get sick”. Yet in a highly complex game world where the player is free to move around and push at the boundaries, a certain amount of jank is unavoidable. As developers perfect photogrammic landscapes and accurate physics, improving their techniques for grounding players in their worlds, occasional bugs will inevitably disrupt the illusion - and lead to more acute nausea. “We almost certainly will have the problems that you’re talking about magnified by the fact that you almost feel like you’re there, and your body engages with the environment almost as if it is real,” Weech says. “But then it’s really not ready to respond to the artifacts that do emerge.” So, are we looking at a vomfest in the years to come? That depends. There are things you can do as a player to reduce nausea. Weech recommends stabilising yourself in the physical world - avoiding exercise balls and beanbags in favour of a steady chair. While you’re at it, open the curtains or keep the lights on - so that “you can see the reference frames around you”. That goes double if you’re using a large screen. “Wait until you’ve got your gaming legs before you expose yourself to long sessions,” Weech says. “Ease yourself into it with easier games, before moving on to the more obviously provocative ones.” Ginger chews or ginger tea can settle the stomach, while cold water can help cool you down: “It’s all about reducing stress to the body and the nervous system.” If you’re tinkering with FOV and other settings, only do so for short periods of time. “Don’t try to push through,” Weech says. “Because otherwise, you’ll associate sickness with this environment. And then every time you go back to the environment, you’re going to feel sick again.” That’s especially common in VR. “If someone gets sick once using a headset, they’ll associate the smell of that headset with sickness,” Weech says. “And then they’ll never be able to use it again, because they often have this very plasticky smell to them.” Above all, do what you find works best for you: “If a certain speed or a certain field of view works, then great, that works. Don’t change it.” It’s reassuring to know that game developers will be doing their utmost to reduce nausea from their end. They are, after all, professional problem solvers. “It’s one of those things that’s pretty easy to combat as a developer,” Oshry says. “There’s really no excuse not to add movement and camera options, it’s pretty standard these days. We’re gonna keep doing it, because the last thing we want is people getting sick playing out games.”